To boldly go where no man has gone before

I’ve been a Star Trek fan for as long as I can remember. Not in the “I own a replica phaser and attend conventions” sense - more in the “I’ve rewatched TNG more times than I can count and I will argue with you about which series is the best” sense. When people ask me why I like Star Trek, I find it hard to give a pithy answer. It isn’t the spaceships or the technobabble. It’s something deeper.

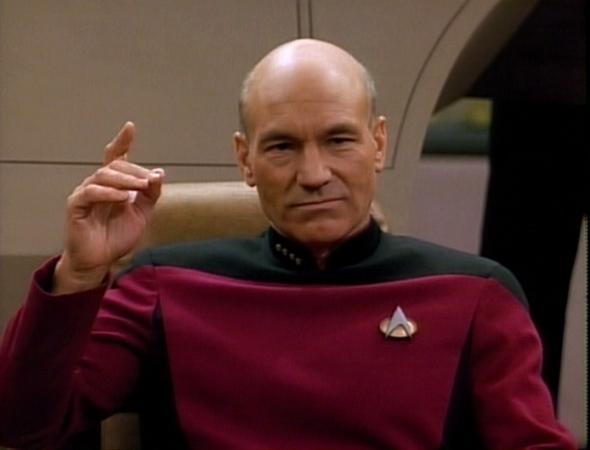

Star Trek, at its best, is a show about ideas. It takes on the thorniest ethical and philosophical questions humanity grapples with, strips away the noise of contemporary politics, and presents them in a distilled, almost pure form. By setting these dilemmas in the 24th century, aboard a starship, among aliens, the show gives you permission to think about them clearly, without the baggage of your tribal allegiances. You end up wrestling with questions about personhood, civil liberties, and communication without even realizing it, because you’re too busy being entertained by a bald Frenchman played by a British actor.

And underneath all of it is a stubborn optimism about humanity’s future. Trek doesn’t pretend that humans are perfect - characters make mistakes, succumb to fear, let prejudice cloud their judgment. But the show insists that these are flaws we can overcome. In a genre dominated by dystopias, Trek’s conviction that the future is bright - that we’ll figure out poverty and war and disease and explore the galaxy out of sheer curiosity - feels almost radical.

Picking Favorites

Picking favorite Star Trek episodes is nearly impossible. There are hundreds across the franchise, and an absurd number are genuinely excellent. “The Inner Light”? “In the Pale Moonlight”? “City on the Edge of Forever”? Every omission feels like a betrayal. But I have to draw the line somewhere.

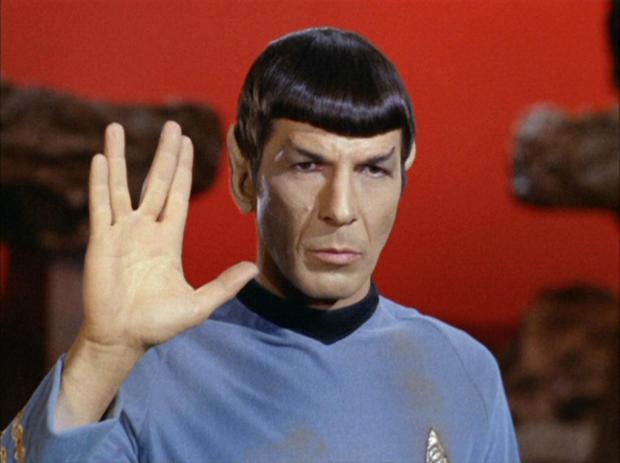

The Next Generation is my favorite series by a wide margin - it’s the Trek I grew up with, and the one that most consistently delivers thoughtful, idea-driven storytelling with characters who feel like adults grappling with genuinely difficult problems. The Original Series comes a close second - it has a rawness and audacity that TNG sometimes lacks, and the Kirk-Spock-McCoy dynamic is one of television’s great character trios. But TNG is home.

The Episodes

The Measure of a Man puts Data - an android - on trial to determine whether he’s a person or Starfleet property. What makes someone a person? Consciousness? Sentience? The ability to suffer? Riker, forced to argue against Data’s personhood, nearly destroys his friend - not out of malice, but because the system demands it. The episode aired in 1989, decades before debates about AI rights became mainstream. But what makes it great isn’t the prescience - it’s the refusal to give you an easy out. The judge doesn’t determine whether Data is sentient, only that he has the right to choose for himself. That nuance is everything.

Darmok is, on paper, one of the strangest episodes of television ever produced. Picard is stranded with an alien captain whose species communicates entirely through metaphor. “Shaka, when the walls fell.” “Darmok and Jalad at Tanagra.” It’s gibberish at first. But as Picard pieces together the meaning - as he realizes Dathon is willing to risk his life to bridge the gap between their species - the episode becomes quietly profound. Understanding is possible, even when it seems impossible, if both sides are willing to try. I can’t think of a more hopeful message.

The Drumhead is the darkest of the four episodes I’m highlighting. Admiral Nora Satie comes aboard to investigate a security breach and spirals into a full-blown witch hunt - McCarthyism in a Starfleet uniform. What’s unsettling is how easily it happens, how quickly fear overrides reason. Picard’s monologue at the climax is one of the finest moments in all of Trek: “With the first link, the chain is forged. The first speech censured, the first thought forbidden, the first freedom denied, chains us all irrevocably.” It’s a warning that feels as urgent now as when it aired.

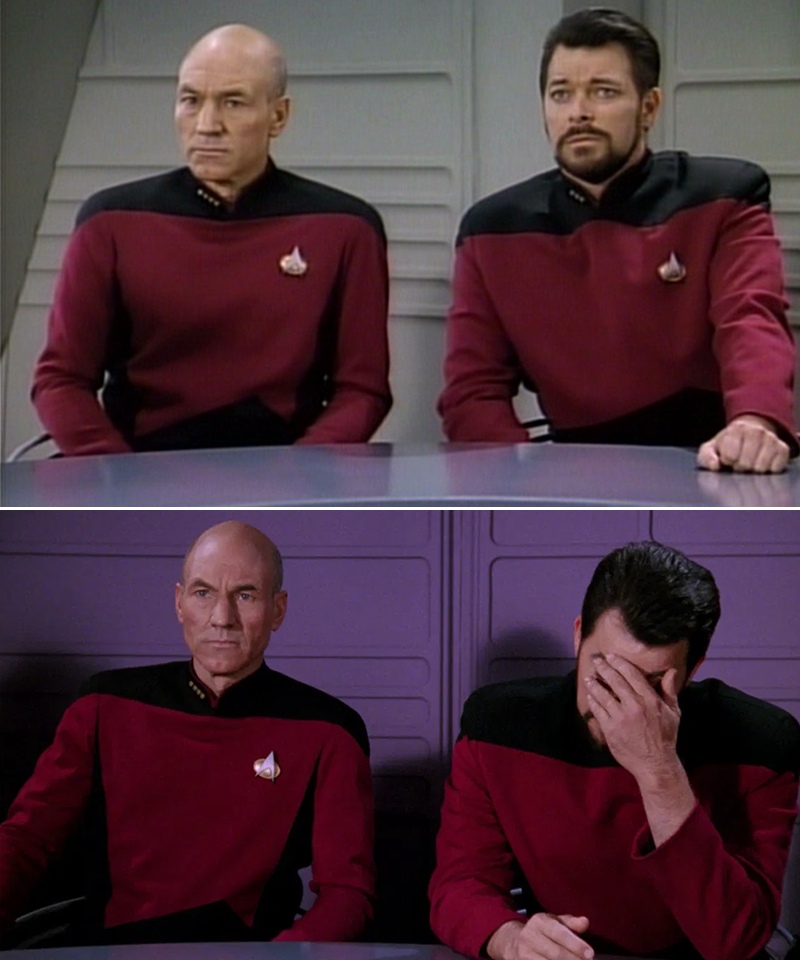

Chain of Command contains some of the finest writing and acting Trek has ever produced. Picard is captured by the Cardassians and subjected to interrogation by Gul Madred. No elaborate contraptions, no over-the-top violence - just two men in a room, one holding absolute power, methodically breaking the other down. David Warner’s Madred is chillingly calm, almost reasonable, as he asks again and again how many lights Picard sees. Four. There are four lights. But the genius is Picard’s confession to Troi afterward: that in the end, he could see five. Madred had very nearly succeeded. Mental torture doesn’t need to leave visible scars. It works by making you doubt your own perception of reality, and the fact that even Jean-Luc Picard can be brought to that edge is what makes it so unsettling. Patrick Stewart’s performance here is the single best piece of acting in the franchise.

What Happened to Star Trek?

These episodes capture everything I love about Trek: the willingness to ask hard questions without pretending the answers are simple, and the insistence that humanity is worth believing in. Which is why the modern reboots have been so disappointing.

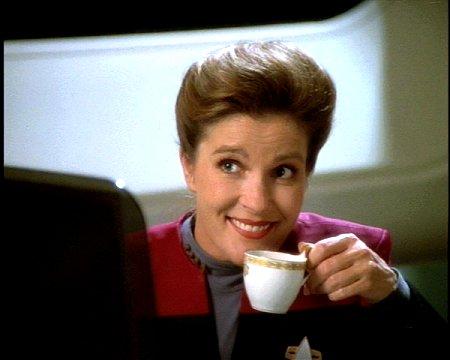

The classic era - TOS, TNG, DS9, Voyager, Enterprise - shared a common DNA despite their differences. TOS tackled racism and Cold War politics head-on when that took real courage. TNG refined the formula into something more cerebral. DS9 complicated Trek’s optimism by asking what happens when ideals collide with war, producing some of the most morally complex storytelling on television. Voyager at its best delivered genuine ethical dilemmas and a crew forged under pressure. Even Enterprise was trying to explore humanity’s first stumbling steps into a larger universe, before the Federation existed to guide them.

What unified them all: ideas first, spectacle second. The effects were often modest - sometimes embarrassingly so - but the writing carried the weight. An episode set entirely in a courtroom, or a single room with two characters talking, could be riveting. The dialogue trusted the audience to think.

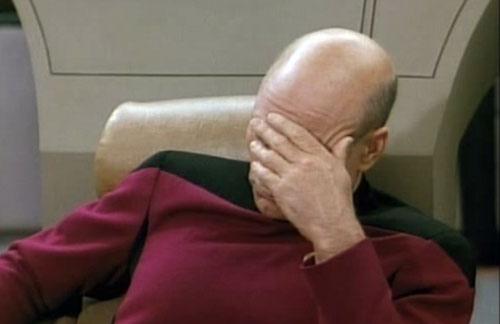

The modern era has inverted this formula. Discovery lost me within its first season. Characters don’t discuss ideas so much as shout their feelings at each other, often laced with profanity that feels jarringly out of place - not because I’m prudish, but because the originals demonstrated you can convey anger and moral outrage without it, and the restraint was part of the point. When Picard dressed someone down, the force came from the precision of his words, not the volume of his voice. Discovery thinks that if a character cries hard enough, the scene earns its emotional weight. It doesn’t work that way.

I gave Picard a fair shot - the entire first season, hoping Patrick Stewart would anchor it in something recognizably Trek. But it felt like a different franchise wearing TNG’s skin: meandering arcs, relentless grimdark, an apparent embarrassment about Trek’s own optimism. I didn’t come back for Season 2. Strange New Worlds and Starfleet Academy I haven’t even attempted. I’ve lost confidence that the current stewards understand what made the franchise special.

The problem is a misdiagnosis of what audiences want. The modern shows believe Star Trek needs prestige-TV production values: sweeping camera work, cinematic CGI, serialized cliffhangers, conspicuously damaged characters. Those things work for other franchises. But Trek was about competent, professional adults solving problems through reason, empathy, and ingenuity. The best episodes are essentially plays: small casts, contained settings, big ideas. You don’t need a $10 million per episode budget for that. You need writers who have something to say.

Flashy camera work doesn’t make you think. A captain staring down a torturer and insisting there are four lights - that makes you think.

The Torch Gets Picked Up Elsewhere

The show that comes closest to capturing classic Trek’s spirit isn’t a Trek show - it’s The Orville. Seth MacFarlane is a massive Trekkie (he cameo’d on Enterprise), and it shows: an exploratory vessel in an optimistic future, a crew that solves problems through diplomacy, an episodic format that gives each installment room for a self-contained idea. It gets what Trek is about in a way the official franchise no longer does.

It does come with baggage. MacFarlane is the Family Guy guy, and that sensibility bleeds through - juvenile humor and cringe-worthy gags that undercut otherwise thoughtful episodes. You’ll be in the middle of a genuine ethical dilemma and someone makes a joke that belongs in a completely different show. I could do with less of that.

But when The Orville commits to the ideas, it commits. “About a Girl” tackles forced gender reassignment on an alien species where all individuals are male and a female birth is a defect to be corrected. The real-world parallels are uncomfortable: female infanticide, intersex surgeries on infants, gay conversion therapy. The episode doesn’t let the crew win - the procedure goes ahead despite their best arguments. It’s the kind of gutsy, morally ambiguous storytelling classic Trek excelled at. “From Unknown Graves” is equally provocative, depicting an absolute matriarchal society where men are subjugated as second-class citizens - flipping a familiar power dynamic and forcing the audience to confront how oppression looks when the roles are reversed. Take a contemporary issue, transpose it into an alien context, let the audience draw their own conclusions. That’s the Trek formula, executed by a show that isn’t Trek.

It’s a strange state of affairs when an affectionate pastiche carries Trek’s philosophical legacy better than the franchise itself. But here we are.

A Final Thought

I keep coming back to Star Trek - the real Star Trek, the Trek of the 60s through the early 2000s - because it offers something almost no other fiction does: the genuine belief that we can be better. Not that we are better, not that progress is inevitable, but that the capacity is there if we choose to do the hard work.

Shaka, when the walls fell. Darmok and Jalad - at Tanagra.